Intro

As a C++ enthusiast, I constantly pursue better performance. Reducing memory copy during returning a value(especially for large objects) is an important but not that well-known topic. I spent some time figuring it out. Today I will try to explain it to you in detail. I will cover a few contents before C++11, but the main focus is the practice under modern C++.

Before C++11

In the old C++ days, only a few techniques are available. One of the most famous ones is return value optimization(RVO) which belongs to a larger category called copy elision. Although it’s not noted in standard, it’s been a significant feature supported by most compilers since C++98. Simply put, RVO is something that eliminates unnecessary copying during construction. I will talk about it later. Remember, it only happens when calling a constructor. Also, unfortunately, it’s not a mandatory optimization at that time, so developers can’t entirely rely on it.

If you want to reduce copy in the assignment, returning value by parameter is a choice. For example,

// former

std::vector<int> join(const std::vector<int>& v1, const std::vector<int>& v2) {

std::vector<int> res;

...

return res;

}

std::vector<int> merged_vec;

if (cond) {

merged_vec = merge(v1, v2);

} else {

merged_vec = merge(v1, v3);

}

In this case, you can’t directly construct a merged_vec from the function. You can do it like this.

std::vector<int> join(const std::vector<int>& v1, const std::vector<int>& v2,

/*output*/std::vector<int>& res) { // or std::vector<int>*

std::vector<int> res;

...

return res;

}

Passing the return value by non-const reference or pointer also reduces unnecessary copy. Sometimes it’s called output parameter, and some people think it’s not a good practice for modern C++. If you’re interested, see TotW #176.

Modern C++

Things become a little complicated starting C++11 since move semantics is introduced. It’s a technique that allows transferring the content of objects other than doing a copy. But I’ll start from RVO because it would still be your first choice.

Take the following code as an example; class Thing will print what is happening.

class Thing {

public:

Thing() { std::cout << "ctor\n"; }

Thing(Thing&&) { std::cout << "move ctor\n"; }

Thing(const Thing&) { std::cout << "copy ctor\n"; }

Thing& operator=(Thing&&) {

std::cout << "move assignment\n";

return *this;

}

Thing& operator=(const Thing&) {

std::cout << "copy assignment\n";

return *this;

}

~Thing() { std::cout << "dtor\n"; }

};

RVO

I have a function returning a local object.

Thing RVO() {

return Thing();

}

Thing thing = f();

ctor

dtor

Note: You could manually disable RVO by -fno-elide-constructors in GCC, but you should also add -std=c++14(or lower) when you use compilers with C++17 or higher as the default standard. I’ll come to it later.

Disable RVO Output

ctor

move ctor

dtor

move ctor

dtor

dtor

You could imagine what the output will look like before the move semantics is introduced, right? When RVO is disabled, three Thing instances are created instead of one.

- A temporary object constructed by

Thing::Thing()in the functionRVO - A temporary object returned by function

RVO, constructed byThing::Thing(Thing&&)(the firstmove ctor) - The object

thingconstructed byThing::Thing(Thing&&)from the second temporary object (the secondmove ctor)

NRVO - Named Version

RVO is called URVO (Unnamed RVO) sometimes since the return object self is unnamed. A named version(NRVO) is triggered when the return object is a named variable. For example:

Thing NRVO() {

Thing thing;

return thing;

}

Thing thing = NRVO();

Output is the same as the RVO.

Guaranteed RVO in C++17

Prior to C++17, compilers only may do RVO if possible. It’s even something you could disable via compiler options. C++17 introduces guaranteed copy elision, and RVO has become a mandatory thing.

So, when using GCC options -fno-elide-constructors std=c++17, the RVO output will be no different. Also, before C++17, even if not called when RVO is applied, an accessible copy/move constructor is required. In C++17, there is no more need for doing so. For example:

class Thing {

public:

Thing() { std::cout << "ctor\n"; }

Thing(Thing&&) = delete;

Thing(const Thing&) = delete;

~Thing() { std::cout << "dtor\n"; }

};

Thing RVO() {

return Thing();

}

Thing thing = RVO();

This code will fail to compile in C++14, but in C++17, it’ll succeed.

However, in C++17, we’ll only get copy elision for RVO, not NRVO. The following code will still fail to compile under C++17.

Thing NRVO() {

Thing thing;

return thing;

}

Thing thing = NRVO(); // Error in C++17

Situations Where RVO is Prohibited

What’s under the hood of RVO is to **use the memory space of the caller’s stack frame to directly construct the object inside the callee function. This effectively removes the need for creating temporary intermediate objects. If you can understand the background mechanism, you can imagine some requirements for RVO.

Undetermined Return Instance

If the returned object is determined when runtime, the compiler can’t decide which one.

Thing NoRVOOne(bool cond) {

Thing a;

Thing b;

return cond ? a : b;

}

Thing thing = NORVO(true);

Note this is only not permitted for NRVO. See the following code:

Thing StillRVO(bool cond) {

return cond ? Thing() : Thing(); // the same even if calling different constructors

}

Thing thing = StillRVO(true);

Return Existing Objects

RVO only happens when the returned object is local. So returning global, static objects or parameters will not trigger RVO.

Thing NoRVOTwo(Thing thing) {

return thing;

}

static Thing thing;

Thing NoRVOThree() {

return thing;

}

Object Slicing

Only a few resources I read mention this point, but it’s also essential. If you want to return a base class from a derived class instance(so-called slicing), RVO is not permitted.

class Derived : public Base {

};

Base NORVOFour() {

Derived derived;

return derived; // slicing

}

Trying to Move the Return Objects

Calling std::move on the return value is incorrect under most circumstances. Doing so will disable possible RVO and force the move constructor. For example:

Thing NORVOFive() {

Thing a;

return std::move(a);

}

ctor

move ctor

dtor

dtor

RVO is not applied here and the move constructor is called. Although the movement is efficient at most times, it still has some cost in-memory operation.

Implicit Move

Another reason for not using std::move when returning a value is whenever RVO is not triggered, an implicit move will be the second candidate, and the plain copy is the last. That’s a compiler trick that returns the lvalue as an rvalue. See example NoRVOTwo

Thing NoRVOTwo(Thing thing) {

return thing;

}

Thing t1;

Thing t2(NoRVOTwo(t1));

ctor

copy ctor

move ctor

dtor

dtor

dtor

The ctor and the second dtor are called by t1. t1 is copied to the argument thing, so the copy constructor Thing(const Thing&) is called. When t2 is constructed, it’s called Thing(Thing&&). You can see no RVO is applied here. The temporary object, lvalue t1 is implicitly moved to t2.

The implicit move is a little bit intrinsic. Requirements for the implicit move are restricted, and things have gotten better in recent years. C++20 introduced the category of implicitly movable entities, and some more PRs related to this topic(like D2266R2) are proposed. I’m not going to expand them here. If you are interested, I strongly recommend you see the talk in CppCon2018 by the author of this PR.

How about the assignment? Unfortunately, there is no corresponding scenario for operator= (nor any other kind of expression or operation). If you call t2 = ImplicitMove(t1), it’s just plain old move semantics since the function call is an rvalue. If you want to reduce the cost of the unnecessary copy, return by pointers is a good choice.

Summary

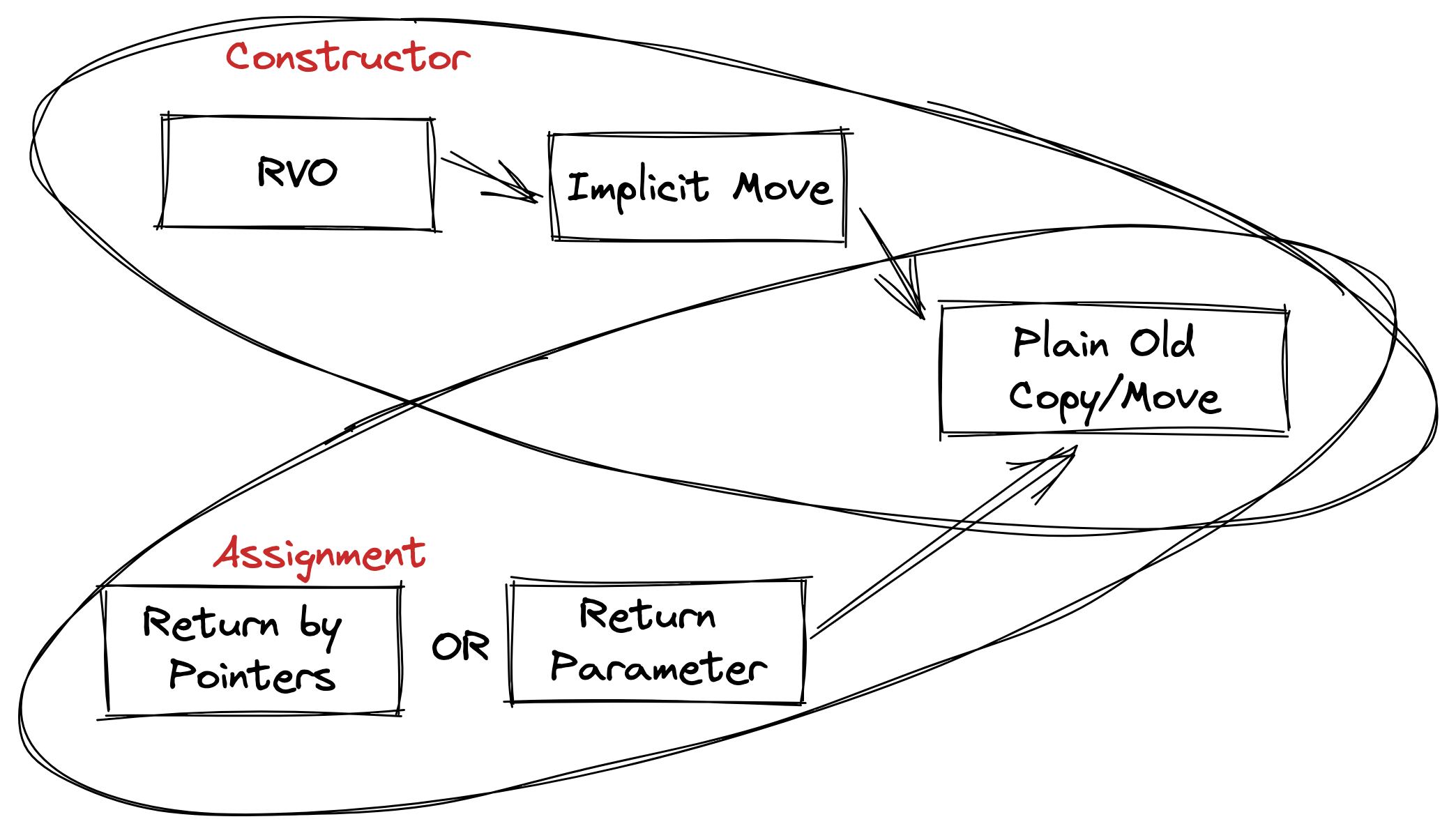

So far, we have reached the primary technique related to returning values in C++. When calling constructor, you should rely on RVO and implicit move; while doing an assignment, try to return a pointer or use the return parameter. I draw a pic for better understanding.